Imagine taking a course in public health and learning about the dangers of air pollution—but not about the historical and current structural and systemic racism and the resulting policies that drive racial segregation in housing and greatly increase the odds that major polluters (from bus depots to chemical plants) will be placed near communities of color. Imagine working for a hospital oncology department and noticing that, unlike white patients, Black patients tend to miss more appointments and have lower remission rates—and then seeing your colleagues nod in agreement as the department director says there is nothing the hospital can do about such disparities.

Unfortunately, these situations are not hard to imagine. They are common. They are, for the more privileged people involved, safe and comfortable. But what about the Black, Latinx, and Indigenous children having asthma attacks? And what about their parents and grandparents dying of cancer far too young? They need us to abandon our positions of relative comfort and to create brave spaces where we can acknowledge difficult realities and work toward solutions together.

Over the past two decades, we—along with many colleagues and community partners—have built spaces just like this, dedicated to dismantling inequities in our communities. Here, we explain our conceptual grounding in cultural competence and cultural humility, provide case studies summarizing our work, and then share lessons learned that we believe could be adapted across a wide variety of healthcare, public health, and educational settings.

Cultural Competence and Cultural Humility

In recent years, professionals in healthcare and public health (as well as many other fields) have recognized the importance of developing cultural competence. From understanding how patients’ concerns are shaped by their cultural contexts to recognizing communities’ strengths and creating environments in which patients feel safe sharing information, it’s likely that the more health professionals know about the cultures of those they work with, the more effective they will be.1 But with such great diversity in many communities across the United States, attaining competence in multiple cultures seems impossible.

While building as much competence as possible remains the goal, our experiences demonstrate that approaching others with cultural humility is an effective means of engaging despite the inevitable gaps in our cultural knowledge. Scholars have defined cultural humility as “a lifelong commitment to self-evaluation and critique, to redressing the power imbalances ... and to developing mutually beneficial and nonpaternalistic partnerships with communities on behalf of individuals and defined populations.”2 Cultural humility requires both introspection and collaboration; it remains hard, even after many years. It also remains well worth the effort and grows even more rewarding over time, as we hope our case studies show.

Our journeys began long before the cultural competence and cultural humility conversation began to pique the interest of health stakeholders or to take root in community-level public health circles. More than three decades ago, pockets of public health enthusiasts were joining forces on local, state, and national levels to address health disparities.3 Much of this work was collaborative, engaging a cross section of participants (i.e., from academic and clinical settings as well as from the community) in community-based public health; it laid the groundwork for universities, communities, and health departments to collaborate on research projects targeting local health disparities, in what is now known as community-based participatory research.4

The early literature indicated that when done well, this type of research tended to create relationship-oriented partnerships that were authentic, lasting, time consuming, layered, and ultimately beneficial.5 Done poorly, community engagement had a very narrow scope and an even less articulated collection of shared expectations. Research projects that claimed community involvement usually issued a “statement of engagement” that had been drafted by researchers without community input and with little else to show for the process. There was no real, meaningful engagement. There was no real commitment. There was no real benefit, at least not for the community.

The need for true community participation became apparent—and that meant grappling with cultural differences so that everyone’s expertise was tapped. Still, the notion of cultural competence caused some uneasiness, in part because of the growing understanding that we cannot ever become truly competent in another’s culture.6 Cultural competence is not something we achieve or fail to achieve; rather, it is a reminder to continue to strive to learn and know more about communities of all types, and especially those we work with or work to impact.7

In our experience, cultural competence and cultural humility together provide health professionals with some of our most important tools in working with diverse individuals, groups, and communities in today’s complex world. Striving toward competence with humility is an exploration, constantly moving, constantly changing, and constantly expanding.8

As we hit our mental rewind buttons and reviewed our own journeys, several fundamental questions began to rise to the surface: What were some of the issues driving the early conversations that oftentimes became spirited debates? In what contexts did they arise? By whom were they sparked? How did we know that we, and our teams, were ready to have these conversations? And most importantly, why were these conversations necessary?

The specific answers to these questions are nuanced, but the broader view reveals one common factor: systemic racism. Without the trauma, fear, guilt, shame, and denial of racism, our pursuit of cultural competence with cultural humility would be stimulating, but not so challenging. The work would require energy, but not bravery.

One important catalyst in this work came in January 1991, when the Kellogg Foundation announced its Community-Based Public Health Initiative. Its aim was to strengthen the practice and teaching of public health by creating partnerships with an informed public. Together, these partnerships were to create sustainable models of a “new” public health through practice, research, and teaching.9 This initiative planted a valuable public health seed that has taken root in several communities across the country and beyond. The two case studies presented in this article have common roots in being two of seven communities nationwide to receive generous funding from the Kellogg Foundation, which recognized the critical role of community engagement in the activities of local public health departments and schools/programs of public health. Several individuals in both of these projects shared experiences and goals, creating a synergy and cross-fertilization of ideas that further enriched each effort.

In the case studies that follow, we focus on our individual and shared journeys: the development of an anti-racism course for public health students at the University of Michigan–Flint (UM-Flint), where Ella Greene-Moton and Suzanne Selig have been collaborating for nearly 20 years, and the systemic transformation of oncology care delivery through the Greensboro Health Disparities Collaborative in North Carolina, in which Eugenia Eng has been a foundational partner.

Although our journeys are quite different, they are anchored in anti-racism and have been guided by the People’s Institute for Survival and Beyond (PISAB), a nationally recognized anti-racism training program.10 As explained in “Building the Foundation for Lasting Social Change” in the sidebar to the right, PISAB’s “Undoing Racism” framework delineates structures built into systems, such as healthcare, that obstruct transparency and accountability for racial equity. Because creating spaces for these conversations is so difficult, we highly recommend finding experienced partners like PISAB to offer guidance.

Case Study 1: Developing an Academic Course in Michigan

This case study, which looks back nearly four decades, describes a university-based anti-racism intervention and the partnership that has been essential to the intervention’s development and sustainability. Today, that anti-racism intervention takes the form of a course, “Cultural Competence in Health Care,” required by the UM-Flint Department of Public Health and Health Sciences for undergraduate health science students (enrolled in health education, health administration, pre-physical therapy, pre-medical, pre-pharmacy, and related degree programs) and master of public health students.

This anti-racism journey began in 1984, when Selig published the results from a five-year study of infant mortality in Genesee County, Michigan, in cooperation with the local health department.11 The purpose of the descriptive study was to better understand the dramatic disparity in infant mortality rates between white and African American babies. Selig and her partners identified geographic “hot spots” for infant deaths in which more prenatal care visits were associated with higher infant deaths. Further inquiries showed that pregnant clients with more visits had had more complicated pregnancies but raised questions about both the what and the how of service delivery. Could there have been something about the nature of the interaction between the pregnant clients and the providers or about the providers’ settings that contributed to infants’ deaths?

At that time, the conventional wisdom was that we needed to get clients into prenatal care sooner and that more visits were better. To facilitate this, and to overcome such barriers as cost and transportation, additional resources were allocated to lengthen clinic hours, open new clinics in areas with high infant mortality rates, and provide transportation. Despite these efforts, the racial disparity persisted.

Selig began to ask: Could implicit bias and racism be playing a role here? Were the clinical staff unknowingly creating an unwelcoming environment for these women? Were women treated respectfully at registration when they arrived late for an appointment? Did the clients who depended on public transit feel safe waiting for buses to attend the clinic? What neighborhood conditions might influence the low utilization of services and high rate of missed appointments?

The Genesee County Health Department invested more resources, including hiring additional staff, and organized a communitywide coalition to address the high infant mortality rate. In 1992, with support from the Kellogg Foundation, the Genesee County Health Department, the University of Michigan (UM), and the city of Detroit formed a public health partnership, bringing to the table faculty from the UM-Flint and UM-Ann Arbor campuses and leaders from local community-based organizations. (As a staff member of the Health Awareness Center, Greene-Moton joined the partnership in 1995.) The Genesee County group began meeting on a regular basis and coordinated with the parallel UM-Ann Arbor partnership with community leaders in Detroit.

The Genesee County partnership faced many challenges. The community group was largely African American, while the university faculty and health department staff members were largely white. It became clear early on that race and racism needed to be addressed for the partnership to be effective as the group struggled with how best to select and order agenda items, rotate meeting facilitators, allocate indirect costs, and foster group cohesion.

Fortunately, several exceptional individuals among the community partners, including Greene-Moton, assumed leadership roles in helping us navigate as we examined the unseen things that divided us. They guided us as we focused on the history of racism in our country and in our communities. We had multiple retreats grounded in the idea that we needed to understand how racism structured our society and our conceptions of ourselves and communities before we could develop the kind of mutual trust and partnership needed to help our communities. The meetings were often tense and contentious—but we finally had hope after three years, when we were unearthing the root causes of the racial disparities in infant mortality (and so many other race-related health inequities).

Through focus groups and discussions with community members, a complex array of potential causes for high Black infant mortality was unearthed:

Local residents attributed infant mortality to the government, parents, the health care system and its practitioners, poverty, and lack of insurance. Government programs were thought to be poorly designed and underfunded. Police were viewed as not doing enough to … stem ubiquitous violence, which cheapens human life…. Parents were viewed as immature and irresponsible about sex…. The health care system was seen as providing insufficient preventive care, as not welcoming to the poor, and as requiring long waits for service. Practitioners were seen as spending too little time with patients, speaking in an incomprehensible technical language and jargon, and failing to make necessary referrals. They were also perceived as discriminatory and racist with a sole interest in the unborn baby to the exclusion of the parents. Local residents also noted that near-poverty leaves little money for insurance and a healthy diet.12

Failing to reduce African American infant mortality during the 1990s, the partnership realized that the true root cause was systemic, pervasive racism.13 In turn, we grasped that in order to substantially reduce infant mortality (and tackle other health disparities), we would have to drive significant social changes.

Despite the termination of the Kellogg funding, which had been instrumental in bringing us together, we recognized that the partnership we had developed was too valuable to disband. Thus, our commitment to the partnership persisted and we continued to meet. When new funding from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) became available in 2000, we were poised to develop a successful multi-year grant application. We built upon the strength and authenticity of our partnership and our collective knowledge of the infant mortality challenges we faced to create an anti-racism campaign for Genesee County. The campaign included a series of PISAB’s Undoing Racism trainings for local hospital administrators and their leadership teams, physicians and other clinic staff, and members of the larger community. Industry leaders and leaders of K–12 and higher educational institutions also participated.

With the work becoming more multifaceted to try to root out systemic racism, Selig, who remained the UM-Flint representative throughout this initiative, proposed the development of a course to help UM-Flint health sciences students focus on self-awareness of their biases and how those biases had developed.* As the director of the Department of Health Sciences, she used her privileged position to achieve the adoption of this course in 2002. Aware of the lack of sensitivity within the university to directly confronting racism, she selected the less threatening title of “Cultural Competence in Health Care,” rather than the more provocative “Racism in Health Care,” with the hope of attracting as many students as possible. As many graduates of the health sciences programs go on to work in the local social service and health sectors, one core goal was for students to share their growing understanding of cultures, biases, and the impact of race with their coworkers and social networks, thus developing students as change agents within the larger community.

A portion of the CDC funding was allocated to UM-Flint, which used the money to hire and support an additional staff member whose primary task was to identify course materials, interactive exercises, and assignments for the students. It also provided funding for Selig to attend a five-day train-the-trainer cultural competence workshop at the University of California San Francisco early in the course development. The planning group determined early on that an African American community member—Greene-Moton—would team-teach the course with Selig.

Over the semester, students participated in many self-reflective exercises. For example, near the beginning of the course, we asked students to think about an early memory of when they felt different from those around them. Some students recalled that they had felt different because of their brown skin, while others mentioned their body size or nonnormative gender behaviors (e.g., a girl who would only wear boys’ clothes). Through this exercise, students realized that at some point in their lives everyone is viewed as different, or othered, and that this experience is often associated with some pain or embarrassment despite the passing of years. We also used an exercise we called “Who am I?” to emphasize that what we see when we first encounter another person is just the tip of the iceberg and that each of us has a multifaceted, complex identity. Each of these exercises was discussed in class in groups of three to five students who shared their reactions and reflections with each other. To deepen individuals’ reflections, we required students to write weekly journal entries that were read only by the instructors. We provided feedback and asked thought-provoking questions like “Why do you think that discussion/comment made you uncomfortable?”

At the same time, students read Beverly Tatum’s book Why Are All the Black Kids Sitting Together in the Cafeteria?15 This easy-to-read book helped students to begin to understand the development of racial identity and the social meaning ascribed to skin color. Many of the students had day jobs, and they reported that reading this book during breaks often led to stimulating conversations with coworkers that might not have occurred otherwise. Throughout the term, most students expressed interest in the content of this book and became more confident engaging in conversations about these topics.

Still, as anticipated, we met resistance, mainly in the form of comments that there was too much focus on race and racism and not enough on other cultures. Some white students began to feel attacked as the cause of racism. This was particularly clear after we watched the documentary The Shadow of Hate, which relates the discrimination, persecution, and near extinction of nonwhite populations in the United States, beginning with Native Americans. It includes history and footage (both reenactments of distant events and real film of more recent events) of painful and difficult topics, including slaughters of Indigenous communities, hangings of Black people in the South, internment of Japanese Americans and other groups during and following World War II, and other atrocities. Many students’ high school history courses had glossed over much of the history of oppression in the United States, so this was the first time the students had been exposed to this information. They expressed both guilt and resistance. “Why has no one told me about this before?” was a common journal entry.

In class discussions, we presented students with models that convey cultural competency as a continuum16 so they could plot their own progress. This, along with an initial in-class assessment, enabled students to mark where they were at that time relative to their knowledge, skills, and awareness. Most students rated themselves as more “competent” and anti-racist at the outset of the course than at the end—which we took as a strong sign of learning. During the course, most students realized how much of their assumed knowledge was inaccurate or incomplete. Students were required to write a final paper based on their previous journal entries, pointing to trends in the successive weekly entries that revealed their own resistance and progress. These papers often mentioned the “Aha!” moments we’d noted in their weekly entries.

With three sections offered per semester, this course has now been taken by over 3,000 students. Although a formal evaluation of this course has not been undertaken, we have much data from the students’ weekly journals, postcourse assessments, and comments on course evaluations. We also have other anecdotal evidence from unsolicited correspondence we have received from students, sometimes many years after they completed the class and graduated. The most common comment is that “this should be a required course for all university students.”

The success of this course is largely due to the solid, respectful, and trusting partnership we developed over many years prior to undertaking this intervention. We have the advantage of a faculty member (Selig), a highly competent staff member (Elizabeth Tropiano), and a community partner (Greene-Moton); each brought expertise, wisdom, history, and experience with racism to the course, giving authenticity to the content and processes. In co-leading the class—and in showing that we value the expertise of lived experience in the community as much as academic credentials—we practice the kind of partnership we hope our students will begin to build. We are also able to model interracial dialogue and express different perspectives in a respectful manner, which has proved invaluable for the students.

Case Study 2: Transforming a Healthcare System in North Carolina

This case study looks back over 25 years—across dozens of partners and processes—to describe the system change that transformed oncology care in Greensboro, North Carolina. Through a multiphase research project in which many collaborators (including Eng) identified barriers to comprehensive care and made step-by-step changes in how patients and providers are supported, we achieved racial parity in cancer outcomes in two settings. Here, both the journey and the resulting oncology care model are shared.

In the mid-1990s, key leaders in Greensboro were eager to form alliances between under-resourced communities and well-established organizations. With the mayor calling for partnerships and a local college and foundation willing to commit to meaningful community-driven change, The Partnership Project (TPP) was formed. A nonprofit dedicated to resolving a wide range of issues related to racial health disparities, TPP remains grounded in Greensboro’s communities. It now has a long history of offering workshops to build people’s capacity to understand and address structural and institutional racism and of building coalitions and strategies to define and resolve specific problems.

Racial disparities in healthcare, well-being, and longevity were on TPP’s radar from the beginning, but they hadn’t gained much traction beyond some healthcare professionals and concerned community members attending workshops. Then, in 2003, inspired by the Institute of Medicine’s report Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Healthcare,17 TPP approached the University of North Carolina (UNC) Gillings School of Global Public Health about tackling Greensboro’s health disparities. Given the report’s description of how racial hierarchies in the United States help explain inequities in the quality of healthcare provided to people of color, TPP’s intent was to increase faculty involvement and engage Greensboro’s communities in community-based anti-racism research that would enhance equity in race-specific health outcomes. More specifically, TPP interviewed three interested UNC faculty as potential collaborators and selected Eng for the planning grant submission that would eventually be called the Greensboro Initiative on the Institutional Dimensions of Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care.

TPP was well prepared for this ambitious project. Since 1997, much of its work had been informed by the Undoing Racism training created by PISAB. The heart of the kind of anti-racism training offered in Undoing Racism is a powerful concept: “The world is controlled by powerful systems with historically traceable roots. Once people are shown how they benefit from or are battered by those systems, they can work together to change the systems.”18 PISAB fleshes this out by showing how structures built into systems, including healthcare, obstruct transparency about and accountability for racial equity.

Working together, TPP staff and UNC faculty quickly saw that PISAB’s analytical approach could guide changes in cancer care. They realized that transparency in oncology and standard healthcare systems is obstructed by

- technocratic protocols that are applied widely to whole classes of patients regardless of their race, normalized by the system’s stability and regular experience, and almost invisible because they seem so ordinary;19 and

- narrow knowledge, which results from training providers and staff to play specialized roles and assigning them to “silos” of specialty divisions or units.20

They also saw that accountability in these areas is obstructed by

- technical language, such as medical jargon, code words, or euphemisms, that enables providers and staff to distance themselves emotionally from the impact of technocratic protocols on patients by disconnecting service delivery from a sense of right and wrong;21 and

- fragmented power that inhibits the capacity of providers and staff to introduce systemwide reform and innovations.22

Based on this analysis, TPP staff and UNC faculty developed a three-phase proposal—consisting of (1) information gathering and anti-racism training, (2) a detailed examination of practices and development of new strategies, and (3) the implementation and evaluation of a new cancer care model—to be carried out over several years.

The local Community Health Foundation awarded TPP $127,573 to complete phase I from September 2003 to February 2005. Phase I established a community-academic-medical task force and engaged members in an anti-racism training; the goal was to form a research partnership that identified variables that appeared to be associated with disparate healthcare outcomes for Black patients in Greensboro and to design a study to determine whether and how these variables contributed to racial disparities in breast cancer care.23 Critical to the success of this phase was the recruitment of 35 task force members (23 community leaders, 6 medical professionals, and 6 faculty), a process that took four months. Each member of this task force, which we called the Greensboro Health Disparities Collaborative, committed to an 18-month involvement with several components:

- Beginning with PISAB’s Undoing Racism training to gain a common vocabulary and understanding of the history and culture of systemic racism in Greensboro and the United States;

- Attending monthly meetings to practice applying PISAB’s racial power analysis to healthcare system change;

- Participating in study design and grant-writing activities to solicit external funding for a community-based anti-racism health disparities project focused on breast cancer care; and

- Deciding at the end of 18 months whether to continue with the work.

During the final eight months of phase I, 17 sessions were led by the TPP-UNC team. We focused on the community-based participatory research approach, identifying factors that contribute to racial disparities in healthcare through a structured exercise of storytelling, analyzing the stories to develop potential research questions, selecting a funding mechanism, determining the healthcare outcome, and working in proposal writing subgroups and a proposal reading subgroup to develop our research project. All of the subgroups included at least one faculty member, at least one health professional, and several community members. The collaborative also convened two meetings with administrators at Greensboro’s cancer hospital (Cone Health Cancer Center at Wesley Long) to elicit feedback and support for the study and request access to breast cancer registry data for the proposed community-based anti-racism cancer health disparities project.

We submitted the project, called the Cancer Care and Racial Equity Study (CCARES), to the National Cancer Institute (NCI) for funding in February 2005. The goal of CCARES was to investigate complexities of how breast cancer care was organized within Greensboro’s cancer hospital, including the nuances of technical language and technocratic protocols, to help explain racial disparities in delay and discontinuation of breast cancer care.24 While awaiting NCI’s decision, the collaborative continued meeting monthly, promoting anti-racism training through outreach education, and developing bylaws so that we could be transparent about our decision-making processes and hold one another accountable in our pursuit of equity as a collaborative.

As phase I wound down, only one of the original 35 members of the task force decided not to continue (due to a budget disagreement). Those who continued crafted and signed a contract to indicate commitment to the collaborative’s guiding principles and mission: to establish structures and processes that respond to, empower, and facilitate communities in defining and resolving issues related to disparities in health.

CCARES was funded in July 2006 by NCI, thus beginning phase II. In this phase, we reviewed the hospital’s breast cancer registry data for 2001 and 2002, focusing on breast cancer treatment delivered to 853 Black and white patients, ages 40 and older, diagnosed with stage 1 or 2 disease. From this registry, 50 patients (46 percent Black, an intentional oversample) were randomly selected to complete two consecutive “critical incident technique” (CIT) interviews with collaborative members, who had been trained in CIT interviewing and analysis.

Here are several key findings that guided our work to develop a new cancer care model.

- Analyzing the registry data, we found racial differences in histological tumor grade, surgical outcomes, insurance status, and physician recommendation of hormone therapy, chemotherapy, and/or radiation therapy. We were not able to examine associations with racial differences in outcomes because cancer registry data did not record hormone receptor status, patient refusal of treatment, dates for initiating and discontinuing or completing treatment, or dates for discontinuing follow-up care.

- In our interviews, the 50 patients described a total of 861 specific encounters as having an impact, positive or negative, on their cancer care experience.

- Both Black and white patients reported most frequently that encounters that contributed to their completing care involved having questions answered, verbally or in writing, by someone in the system.

- For Black patients, encounters for managing side effects or complications from treatment had strong positive impact. For white patients, being satisfied with their interactions with doctors and staff had strong positive impact.

- Our interviews also revealed that 14 patients (4 Black) had delayed or discontinued their treatment or follow-up care, and they described 252 encounters related to these decisions.

- The encounters reported most frequently by Black patients involved inattention to personal and emotional reactions to disease and treatment and minimal or no consideration for financial/insurance constraints.

- White patients were most often negatively impacted by inadequate management of side effects or complications from treatment.

These findings revealed shortcomings in the cancer registry data related to which patients delayed or discontinued their breast cancer care. As to why, the CIT findings described subtle but important racial differences in impacts of patient encounters with the various systems of care. Overall, phase II pointed to the need for prospective studies that record patient encounters with the various systems of cancer care during treatment to identify systemic causes for less-than-optimal care for Black patients.25

Based on these findings, the collaborative began in June 2009 to design a healthcare system change intervention to reduce racial disparities in the quality and completion of early-stage cancer treatment. Collaborative members expressed two concerns: (1) by confining the study to breast cancer patients, the effect of racism could be eclipsed by sexism in the cancer care system; and (2) the cancer hospital in Greensboro is not attached to an academic center, which could limit the transferability of our study’s findings. Hence, we decided to include early-stage lung cancer patients and to add a second site, the Hillman Cancer Center at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center (UPMC), where a postdoctoral fellow who had worked on CCARES had secured a faculty appointment.26

Phase III was the intervention trial, called Accountability for Cancer Care Through Undoing Racism and Equity (ACCURE). It was funded in June 2012 by NCI. This five-year study used information gleaned from patients in CCARES to develop a system-change intervention to address disparities in completion of care for white and Black breast and lung cancer patients with stage 1 and 2 diagnoses. The additional site allowed us to compare an academic research cancer center (UPMC) in a large northern city with a regional cancer center (Cone Health) in a small southern city. If found effective in both locations, the intervention might have transferability to other healthcare systems.

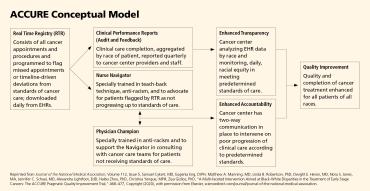

The collaborative followed the community-based participatory research approach and used anti-racism principles of accountability and transparency to design the ACCURE intervention; community, academic, and medical partners shared power in every step of the process so that academic and community perspectives and priorities were carefully integrated.27 As displayed in the ACCURE Conceptual Model diagram below, this anti-racism intervention focused on improving the quality and completion of care in these systems for all patients, regardless of their race.

The intervention had four specific components:

- Real Time Registry: ACCURE applied meaningful use of electronic health records (EHRs) to the system’s problem of incomplete data. We developed a real-time warning system derived from EHRs, downloaded at the end of each day, to identify patients who missed appointments and those who were not on schedule to reach anticipated milestones in standards of care. The next morning, when the ACCURE nurse navigators (described below) logged into the real-time registry, they would be able to see which patients the system had flagged for follow-up.

- Clinical Performance Reports: To ensure that EHR data were analyzed by race, the ACCURE physician champions (described below) distributed quarterly clinical performance reports about patients’ missed appointments and treatment milestones, broken down by race, to clinical teams.

- Nurse Navigators and Physician Champions: To improve communication between and among patients, nurses, and doctors, each site had an ACCURE nurse navigator and physician champion specifically tasked with advocating for patients. They completed PISAB’s Undoing Racism workshop and were specially trained in particular systemic barriers and beliefs that can limit care for Black patients; they were also trained on how to use the real-time registry.

- As the ACCURE model was being implemented, six equity education and training sessions were held with medical and administrative staff. These sessions allowed the ACCURE team to report progress, including preliminary findings, and elicit feedback. These sessions also covered anti-racism concepts such as implicit bias and institutional racism.28

The ACCURE study was a pragmatic trial designed to provide results that could be applied to real-world clinical practice. It was community-based, used broad enrollment criteria, involved treatment by usual care providers in typical cancer care settings, and used study tools and personnel that could easily fit routine clinic workflows. ACCURE also included an embedded randomized controlled trial. Results showed both higher rates of completion of care among Black and white patients and success in closing the gap in completion of care for Black and white patients. At baseline, 87.3 percent of white patients had completed cancer treatment as compared to 79.8 percent of Black patients, which was statistically significant. After the intervention, 89.5 percent of white and 88.4 percent of Black patients completed treatment, which was not statistically significant (indicating parity).29

Phase III was completed in March 2018. The collaborative continues to work with both sites to sustain the ACCURE intervention so that it can be applied to the entire cancer center population, adapted for treatment of other cancers that require more modalities and steps, and expanded to more chronic conditions (such as anti-estrogen therapy in breast cancer) and to the management of other chronic diseases. The collaborative also continues to advocate for system changes to eliminate impacts of racism in other ways.

Lessons Learned

From these two cases of community-driven anti-racism partnerships, we draw the following five lessons, which we believe are transferable to other settings, populations, and public health issues.

Remain community focused and value all participants’ expertise. When the intention is to guide the development of a collaboration to document and address the impacts of systemic racism, consider following the principles of community-based participatory research:30

- Design interventions with the community to enhance knowledge and promote change in ways that benefit the community;

- Establish norms of partnership that emphasize mutual respect and recognition of the knowledge, expertise, and resource capacities of all partners in the process; and

- Be committed to engaging in open communication.

In Michigan, one of the main objectives of the academic course was to prepare students to be change agents in communities to promote anti-racism initiatives. A member of the local African American community (Greene-Moton) brought her community knowledge and lived expertise into the classroom in her role as co-instructor, which added to the authenticity of our interracial dialogue. In North Carolina, the Greensboro Health Disparities Collaborative explicitly employed community-based participatory research principles regarding decision-making power and governance when developing its bylaws and when proposing, designing, and implementing its anti-racism research project.

Create a brave space, in which cultural humility is practiced and nurtured, by anticipating and embracing disagreements and recognizing that conflict is necessary for meaningful change to occur. After the members of the North Carolina collaborative’s phase I task force developed and signed a Full Value Contract documenting their commitment to the collaborative’s mission, that process continued annually. By signing, collaborative members indicated their commitment to the partnership’s 15 core values: conflict, humility, mutual respect, a willingness to stay at the table, speaking from our own experience, perseverance, teamwork, humor, critical listening, accountability to team members and to the team, fun, honesty, a willingness to be uncomfortable, confidentiality, and acknowledgment of people’s strengths. These values were an explicit reminder of how to accomplish the goals that we set together. The Michigan partnership practiced cultural humility and encouraged respectful conflicts within the classroom. Although the specific issues vary with each group of students, every time the course is taught the students are engaged in developing ground rules for open, civil discussions of disagreements.

Establish and work from a common vocabulary of anti-racism to enable discussions of structural racism and white supremacy. Members of the partnerships in both Michigan and North Carolina completed anti-racism workshops conducted by the People’s Institute for Survival and Beyond. For the collaborative, the rationale was that in order to study the historical origins and current manifestations of systemic racism, members needed to gain a common language and vocabulary. For health disparities researchers and practitioners, studying racism is as essential as studying biology is for medical scientists and clinicians. To this day, completing anti-racism training is required for new members to join the collaborative. For the Michigan course, the planning team found the Undoing Racism workshops invaluable for thinking through both the content of the course and the most respectful processes for encouraging discussions of highly charged topics. In addition, students in the course have been invited to complete anti-racism training to deepen their understandings and, thereby, reduce resistance to concepts such as white privilege and internalized racial inferiority.

Elevate the community voice to leadership roles within the partnership; recognize community partners’ needs and make the work sustainable, while holding all partners accountable. For the course, a community member was (and still is) a paid co-instructor serving as a liaison between the instructional team and community partners. For the collaborative, the bylaws stipulate that the chair position can be filled only by a community partner, and all committees (e.g., outreach, membership, publications, social media, and ad hoc) must include community partners.

Recognize that these partnerships are fluid and dynamic, reflecting continual changes in membership and requiring orientation and reorientation while also necessitating institutionalization of processes. As the demand for the Michigan course increased, new instructor pairs were hired. The selection process included an orientation to ensure that the instructors had the experience and commitment to fulfill the objectives of this course. The North Carolina collaborative amended its bylaws to establish a “Friends of the Greensboro Health Disparities Collaborative” membership category for those who experienced a life course transition, such as retirement or illness, and could no longer be fully active. Friends still receive collaborative minutes and mailings. For new members, the collaborative’s Membership Committee developed an orientation video on the partnership’s history and a “buddy program” to pair each new member with a current member.

We began this writing journey recognizing an opportunity introduced through the Community-Based Public Health Initiative in 1991, which planted enduring seeds in our communities. These models advocated for an engagement between academia, public health practitioners, and communities, brokering relationships that would inevitably grow into lasting partnerships. We found that these partnerships were most often formed and bounded by deliberate practices and guidelines developed and adopted by all the participants in those groups, based on shared language and agreed-upon values. The synergy that resulted was the product of our hard work and our commitment to the partnership, which were possible because we recognized that “we are stronger and better when we work together.”31

Ella Greene-Moton is the administrator for the Community-Based Organization Partners (CBOP)–Community Ethics Review Board (CERB). Suzanne Selig, professor emerita of public health and health sciences, is the former director of the Department of Public Health and Health Sciences in the University of Michigan–Flint College of Health Sciences. Eugenia Eng is codirector of the Cancer Health Disparities Training Program and a professor in the Department of Health Behavior at the Gillings School of Global Public Health at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

*While the remainder of this case study focuses on the course, the anti-racism campaign in which this course is grounded is proving beneficial. Although there is still a disparity in Black and white infant mortality rates, those rates have been trending downward for several years14 and our coalition of healthcare, public health, and community partners remains actively dedicated to strategies for addressing systemic racism. (return to article)

Endnotes

1. R. Castillo and K. Guo, “A Framework for Cultural Competence in Health Care Organizations,” Health Care Manager 30, no. 3 (2011): 205–14.

2. M. Tervalon and J. Murray-Garcia, “Cultural Humility Versus Cultural Competence: A Critical Distinction in Defining Physician Training Outcomes in Multicultural Education,” Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved 9 (1998): 123.

3. W. K. Kellogg Foundation, An Overview of the Community-Based Public Health Initiative (Battle Creek, MI: W. K. Kellogg Foundation, 2001).

4. B. Israel et al., “A Review of Community-Based Research: Assessing Partnership Approaches to Improve Public Health,” Annual Review of Public Health 19 (1998): 173–202; and A. Schulz et al., “The Research Perspective: Development and Implementation of Principles for Community-Based Research in Public Health,” in Community-Based Public Health: A Partnership Model, ed. T. Bruce and S. McKane (Washington, DC: American Public Health Association, 2000), 53–69.

5. J. Barnes et al., “Creating and Sustaining Authentic Partnerships with Community in a Systemic Model,” Journal of Higher Education Outreach and Engagement 13, no. 4 (2009): 15.

6. V. Chavez, “Cultural Humility: Reflections and Relevance for CBPR,” in Community-Based Participatory Research for Health: Advancing Social and Health Equity, ed. N. Wallerstein et al., 3rd ed. (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2018); and M. Minkler, C. Pies, and C. Hyde, “Ethical Issues in Community Organizing and Capacity Building,” in Community Organizing and Community Building for Health and Welfare, ed. M. Minkler, 3rd ed. (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2012), 110–29.

7. M. Isaacson, “Clarifying Concepts: Cultural Humility or Competency,” Journal of Professional Nursing 30 (2014): 251–58.

8. E. Greene-Moton and M. Minkler, “Cultural Competence or Cultural Humility?: Moving Beyond the Debate,” Health Promotion Practice 21, no. 1 (2019): 142–45; and S. Selig, E. Tropiano, and E. Greene-Moton, “Teaching Cultural Competence to Reduce Health Disparities,” Health Promotion Practice 7, no. 3 suppl. (2006): 247S–55S.

9. Kellogg Foundation, An Overview.

10. I. Shapiro, Training for Racial Equity and Inclusion: A Guide to Selected Programs (Washington, DC: Aspen Institute, 2002), aspeninstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/files/content/docs/rcc/training.pdf.

11. S. Selig, “Infant Mortality 1978–1982, the Genesee County Matched Record Study” (unpublished manuscript distributed by Genesee Child Health Council, June 1984).

12. R. Pestronk and M. Franks, “A Partnership to Reduce African American Infant Mortality in Genesee County, Michigan,” Public Health Reports 118, no. 4 (2003): 328.

13. Pestronk and Frank, “A Partnership to Reduce.”

14. Pestronk and Frank, “A Partnership to Reduce”; and Genesee County Health Department, “Vision—Genessee County: Thriving Communities Embracing a Culture of Health: Data Review,” Genesee County Maternal Child Health Network, June 22, 2017, gchd.us/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/GCMCHN-Data-Review-Presentation-Final.pdf.

15. B. Tatum, Why Are All the Black Kids Sitting Together in the Cafeteria? (New York: Basic Books, 1997).

16. T. Cross and M. Isaacs, Towards a Culturally Competent System of Care: A Monograph on Effective Services for Minority Children Who Are Severely Emotionally Disturbed (Washington, DC: CASSP Technical Assistance Center, Georgetown University Child Development Center, 1989); and M. Bennett, “Towards Ethnorelativism: A Developmental Model of Intercultural Sensitivity,” in Education for Intercultural Experience, ed. R. Paige (Yarmouth, ME: Intercultural Press, 1993).

17. B. Smedley, A. Stith, and A. Nelson, Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care (Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2003).

18. Shapiro, Training for Racial Equity.

19. G. Adams and D. Balfour, Unmasking Administrative Evil (Armonk, NY: M. E. Sharpe, 2004).

20. L. Trubek and M. Das, “Achieving Equality: Healthcare Governance in Transition,” American Journal of Law and Medicine 29 (2003): 395–421.

21. Adams and Balfour, Unmasking.

22. Trubek and Das, “Achieving Equality.”

23. M. Yonas et al., “The Art and Science of Integrating Undoing Racism with CBPR: Challenges of Pursuing NIH Funding to Investigate Cancer Care and Racial Equity,” Journal of Urban Health 83 (2006): 1004–12.

24. Yonas et al., “The Art and Science.”

25. E. Eng and C. Hardy, “Cancer Care and Racial Equity Study: Interpreting Findings and Getting to Outcomes with Patients, Their Medical Care Providers, and Communities” (presentation, Lifespan Symposium of the UNC Translational Research and Clinical Services Institute, Chapel Hill, NC, March 2010).

26. E. Eng et al., “Partnership, Transparency, and Accountability: Changing Systems to Enhance Racial Equity in Cancer Care and Outcomes,” in Community-Based Participatory Research for Health, ed. N. Wallerstein et al., 3rd ed. (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2017).

27. J. Schaal et al., “Community-Guided Focus Group Analysis to Examine Cancer Disparities,” Progress in Community Health Partnerships 10, no. 1 (2016): 159–67.

28. K. Black et al., “Antiracism Organizing for Culture and Institutional Change in Cancer Care,” in Racism: Science and Tools for Health Professionals, ed. C. Ford et al. (Washington, DC: American Public Health Association Press, 2019).

29. S. Cykert et al., “A Multi-Faceted Intervention Aimed at Black-White Disparities in the Treatment of Early Stage Cancers: The ACCURE Pragmatic Quality Improvement Trial,” Journal of the National Medical Association 112, no. 5 (October 2020): 468–77.

30. Schulz et al., “The Research Perspective.”

31. C. Coombe et al., “A Participatory, Mixed Methods Approach to Define and Measure Partnership Synergy in Long-Standing Equity-Focused CBPR Partnerships,” American Journal of Community Psychology 66, no. 3–4 (2020): 427–38.

[Illustrations: Mia Nolting]