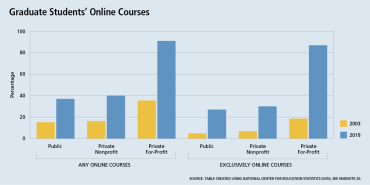

Between 2003 and 2016, the percentage of undergraduates taking at least one course online nearly tripled, increasing from 15.6 to 43.1.1 Initially, that enrollment was concentrated in the proprietary, or for-profit, higher education sector. In response, and to make up for declining numbers of “traditional” college students and the resulting revenue shortfalls, some public colleges and universities formed arrangements with for-profit education companies.*

While these arrangements take many forms, here’s an example: in 2017, without faculty input or approval, Indiana’s Purdue University acquired for-profit online giant Kaplan University, creating one of the largest online providers in the country.3 The arrangement changed Kaplan’s name to Purdue University Global and locked the newly formed institution into a long-term service agreement with Kaplan’s for-profit holding company. The institution birthed from the deal, Purdue Global, has been a captive client of its for-profit service provider since day one and has been prevented from acting in the best interest of its students.4 It relies on Kaplan’s holding company to function, and Kaplan retains veto rights over academic and admissions changes proposed by Purdue Global. If Purdue Global wants to continue existing, it must continue to rely on Kaplan’s services. Further, in Purdue’s contract with Kaplan, Purdue agreed to continue Kaplan’s tradition of overspending on marketing and recruiting and overcharging students in tuition and fees.

Other similar arrangements have captured the media’s attention in the past two years.5 In 2020, the University of Arizona announced that it would acquire the notorious for-profit giant Ashford University. Ashford is known to student and consumer advocates because of its dismal track record: Ashford spends an abysmal $0.19 on instruction for every tuition dollar it collects.6 (In contrast, the median for-profit institution spends $0.38, the median private nonprofit institution spends $0.59, and the median public institution spends $1.29 on instruction for every dollar collected in tuition.7) Ashford’s students have suffered from the lack of investment in their success—just 24 percent return after their first year and the graduation rate is only 22 percent.8 In 2021, Ashford’s accreditor, the Western Association of Schools and Colleges, sent the school an action letter demanding it revise and clarify its plans for academic improvement.9 Ashford has also faced a series of lawsuits and investigations for violating several states’ consumer protection laws and has been sued for fraud by the state of California.10 As yet, it is unclear how or if the University of Arizona plans to clean up Ashford’s operations, or if it is simply sticking its name onto a subpar product and using the revenue to subsidize other parts of the system’s operations.

These high-profile arrangements operate in much the same way as lesser-known—but more common—partnerships between many of the nation’s oldest, most respected colleges and universities and for-profit, third-party providers. Private education companies, often referred to as online program managers (OPMs), manage hundreds of online degree programs for public colleges and universities, though the public—including the students and faculty in the programs—is too often unaware. Many flagship state universities have or have had contracts with OPMs (including Arizona State, Kent State, Louisiana State, the University of Florida, and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill), though colleges and universities of all sizes and missions engage in this form of academic outsourcing.11

OPMs offer services from student recruitment to video production to instructional design. Despite these college-OPM arrangements operating in the background, they can be just as big of a liability as Purdue’s deal with Kaplan and Arizona’s arrangement with Ashford. Schools that contract OPMs for a comprehensive set of services can find themselves stuck in never-ending arrangements that serve neither students nor their bottom line, for a variety of reasons.

The arrangements behind the scenes of many online degree programs are billed as public-private partnerships, a concept that has long been the darling of liberal and neoliberal education reformers. These partnerships are promoted with and hinge on the idea that the private sector can innovate and operate more efficiently, so pairing that potential with a public good enhances outcomes for the public. Public-private partnerships can be found up and down the education sector and throughout the typical campus, where they are relied on for housing, dining, maintenance, and parking services. In reality, such partnership billing is meant to sugarcoat what is really happening: outsourcing. In many respects, colleges and universities in these arrangements have outsourced their core functions and shifted control of a public good into the hands of private, for-profit companies.

The Perfect Storm: Privatizing Public Higher Education

Outsourced academic programs are really privatized programs. Privatization supplants the public purpose with private gain, which further erodes the structure of public colleges and universities. Multiple factors have contributed to the perceived need to outsource core functions.

The most important is that public institutions are starved for funds. After the Great Recession,12 public colleges and universities never truly recovered to their pre-2008 levels of public support and subsidy: nationally, state and local funding for public higher education’s operating expenses in fiscal year 2020 was 6 percent below the 2008 funding level and 14.6 percent below the 2001 funding level.13 To add insult to injury, the burden of insufficient funding is not equitably distributed. Community colleges and historically Black colleges and universities have always had some of the lowest levels of per-student support and have therefore been made to do more with less.14

Credentialism is another factor in the perfect storm that has led colleges and universities to outsource programs. Credentialism is the way a degree or certificate signals job worthiness, rather than actual skill level, and it increases demand for credentials as people seek better jobs and/or more security against layoffs.15

Closely related to this drive for credentials are inflation plus stagnant wages.† Our salaries provide us less than they did 10 and 20 years ago;16 job seekers can infer that a higher credential might get them a higher paying job, which also drives up demand for higher education programs.

At the same time, student loan debt has remained a steady, accessible form of credit. For-profit colleges have a long history of preying on those most in need of credentials, particularly African Americans:

Government-backed student loans were opened up to students at for-profit colleges in 1972 and quickly became integral to these schools’ business models. For-profit schools began to market themselves to students of color specifically by helping them navigate the federal student loan system.... For-profit schools’ ability to attract students was given a significant boost by the 2008 recession, when young people sought refuge from a weak labor market in degree programs.... Greater demand for higher education is typical during a recession, but recent research argues that this trend was exacerbated in 2008 by a monopsonized labor market (i.e., a labor market dominated by too small a number of employers), in which employers could demand more credentials for the same jobs. This was particularly harmful for students of color, from whom employers already demanded higher credentials.17

Squeezed by inadequate government funding and seeking to capitalize on this demand, public colleges and universities have responded by outsourcing their core functions in hopes of quickly drawing in new students. Far too many students have no idea a private company is behind the ads they see, the recruitment calls they receive, and the management of the program they eventually enroll in. The profit-oriented ethos of these OPMs has eroded the democratic ideal of public higher education as a key institution contributing to our ability to self-govern.18

Grad School Cash Cows: Creating the Outsourced University

In 2019, over half of all graduate degrees earned were concentrated in three fields: business, education, and health. Universities have enjoyed robust demand for these degrees thanks to a convergence of factors, including that educators and health professionals can earn a salary increase and/or gain access to specialized roles with increased training. The number of graduate health professions degrees conferred between 2009 and 2019 nearly doubled (from 69,100 to over 131,600), while the number of graduate education degrees granted during that period dropped from its peak of over 180,000 to holding steady near 150,000 per year.19

Graduate schools of education and health are an essential part of the public university ecosystem. Even so, thanks to economic pressures, public universities rely on full-paying graduate students as a source of revenue. While this cash-cow situation emerged on public university campuses, for-profit colleges also cashed in by marketing online graduate degrees on a national scale.

Such cash-cow programs are not necessarily low in value for students. Graduate programs are worthwhile to educators and health professionals even beyond potential pay increases and promotions. Graduate-level training is valuable for the professional networking opportunities and for the application of higher-order, research-based practices in the field. However, there has been a risk of that value decreasing ever since the nation’s public colleges realized they could fatten their cash cows by competing with for-profit, online mega-universities.

Between 2003 and 2019, the percentage of graduate students in public universities earning their degrees online grew from 4.8 to 27.20 For public universities, one goal has been to attract students who might otherwise go to the for-profit behemoth University of Phoenix. At its peak in 2010, the University of Phoenix enrolled nearly half a million students. According to some University of Phoenix insiders, its growth came at the cost of quality control measures that had been in place a decade prior.21 By the time public and nonprofit colleges and universities entered the online degree game, the University of Phoenix brand was tarnished because of high withdrawal rates, low graduation rates, and high student debt.22 For recognizable public universities, attracting students away from the scandal-plagued for-profit college sector is not difficult; the challenge comes with legitimately offering an experience that is of higher quality and value than one would find at schools like the University of Phoenix.

OPMs have been experiencing a prolonged boon thanks to enrollment- and revenue-anxious institutions that feel the need to quickly create online programs. Some of the anxiety is justified. Pressure to compete online can come from governing boards and state legislators who want their institutions seen as national leaders in an increasingly crowded “global U” arena. This pressure also comes from a basic need to generate revenue because of the low levels of public funding.

Steady demand in certain fields, coupled with enrollment and revenue shortfalls in other fields, has added to the perfect storm for the proliferation of online and outsourced graduate degrees. Because graduate education and health degrees have long been a safe bet, it is no surprise that when public universities began offering online degrees, they started with those fields. Many of the contracts signed by public universities to initiate partnerships with OPMs began with one, two, or a handful of education or nursing programs and ballooned from there.23

When OPMs entered the scene as enablers, they offered to front the costs and risks associated with launching online programs in exchange for a substantial cut of the tuition revenue (often around 50 percent and sometimes up to 80 percent).24 Many universities are still locked into the terms of those early “partnership” agreements—some dating back over a decade—because OPMs could justify long terms and difficult exit clauses by the amount of risk they were taking on. Resources must be devoted to designing and launching an online program, but if students don’t fill the virtual classrooms, the upfront investments are lost. OPMs purport to take on that risk by facilitating the creation and marketing of, and recruitment to fill seats in, online courses.

While there are very real risks on the OPM side, they diminish as the partnership matures and as the OPM takes on more partners. This is because OPMs enjoy efficiencies across the services they offer and the clients they serve. OPMs can find and exploit efficiencies in two key directions: by managing the same program across multiple institutions and by managing multiple programs for single institutions. In the case of the former, the OPM takes on less risk with each duplicate program it manages; the necessary details for the curriculum development and instructional design stages, for example, are largely replicated across campuses. In the case of an OPM managing multiple programs for a single institution, the labor involved with branding, marketing, and recruitment work will be lighter with each program added to the scope of an OPM-university contract.

An OPM called Academic Partnerships manages or has managed graduate education programs for public universities including Eastern Michigan University, Louisiana State University Shreveport, and the University of West Florida. According to their contracts, Academic Partnerships has a hand in curriculum development, program sequencing, instructional design, program marketing, and student recruitment.25 So while the brand under which degrees in programs like educational leadership are offered may be different, the content and marketing strategies happening behind the scenes are not.

In the early days of online program enablement, OPMs did take on quite a lot of upfront risk. But today, there is no reason for a public university to lock itself into a long-term contract that outsources its core functions to a for-profit provider. Given the current balance of risks and efficiencies, universities are in a much more powerful negotiating position for securing shorter contracts with easier exit clauses. Exercising that power increases the value of the partnership for students, faculty, and the public at large.

The Oversight Triad: Playing Catch-Up

Among those colleges and universities in which the perfect storm holds true, using an OPM to make up for revenue shortfalls is like expecting an umbrella to keep you dry while walking through a hurricane. Public and nonprofit colleges and universities should be looking to more effective and sustainable responses to the storm they find themselves in. That may mean assessing what the local community and economy need and exploring how to bring education to any nearby communities in education deserts using internal expertise and community input. To realize the true democratic ideal of public higher education, its programs should serve more than its bottom line. Under the OPM status quo, programs currently serve the bottom lines of third-party companies first, the college or university second, and the students third, if at all.

In theory, higher education is regulated by a triad of oversight consisting of the federal government, states, and accrediting agencies. Despite this, online—and especially outsourced—degrees are largely unregulated. This is the case for a number of reasons, and in the online graduate program marketplace, a major factor is a decade-old loophole.

Colleges and universities are prohibited from paying employees or contractors who recruit students for programs per head they successfully enroll. This is an important ban that protects prospective students from pressurized sales tactics that masquerade as student recruitment. If recruiters can be paid on a commission basis, they have an incentive to do whatever it takes to secure students’ enrollment. In 2011, however, the US Department of Education created an exception to this ban, allowing colleges to pay contractors who provide a bundle of services, including student recruitment, on a tuition-sharing basis.26 The department justified the loophole on at least two bases. One, that the third party would remain independent from the institution and wield no influence over decision making—and thus would not be prone to the same abuses that had been previously documented within the for-profit college sector. Two, that public and private nonprofit colleges and universities needed an exception to the ban on incentive compensation payments in order to offer online programs and provide an alternative to students who would otherwise look to the for-profit online giants.27

Unfortunately, this ushered in the growth of a massive industry of for-profit providers that operates behind the scenes of hundreds of degree programs and is reliant on public funding.28 Worse, many OPMs and their college and university partners have ignored the guidance that provides the exception in the first place. Under some agreements, OPMs have decision-making power over enrollment, tuition pricing, budgeting, and curricular matters.29 For example, a public university in Texas relies on an OPM to manage dozens of online programs; as part of the agreement, a steering committee made up of equal parts university and OPM representatives meets regularly to discuss items like admission policies and how policy changes impact the revenue the programs bring in.30

Other parts of the oversight triad that could step in to minimize potential harm to students have yet to do so effectively. Accreditors are still getting their bearings when it comes to understanding the OPM industry and how they should review arrangements between their member institutions and the private companies.31 Unfortunately, while they take time to catch up, some very problematic arrangements have formed, showing the extent to which public colleges and universities can truly be diluted by their “partners” from the private sector. For example, Grand Canyon University has an OPM-style service contract with its for-profit counterpart, Grand Canyon Education.32 The two Grand Canyon organizations share a CEO, and the nonprofit university is a completely captive client, locked into an infinite contract with the for-profit company. This captivity was created by design, though many other colleges and universities are approaching a similar level of capture by their OPMs, despite arriving there from a different starting point.33

OPMs now hold power over things like tuition pricing, enrollment targets, and program governance at many public institutions. At those where OPMs have become the most embedded, to pull the plug on them would threaten the viability of the institution itself. When private power outweighs public power, it is not a partnership at all.

Recentering the Public in Public-Private Partnerships

As they are currently operating, many outsourcing arrangements between public colleges and universities and for-profit OPMs are eroding the democratic ideal of public higher education. Public institutions are at risk, and so are many of the students bringing the necessary tuition dollars. Faculty and the campus community can and should step in to reclaim the public’s role and the public’s benefit in these so-called partnerships.

In 2019, the American Association of University Professors (AAUP) distributed a toolkit to assist its chapters in scrutinizing arrangements that privatize the online classroom.34 The guide was compiled based on lessons learned by AAUP chapters that had encountered problematic features in their universities’ OPM contracts, as well as from 2017 and 2019 analyses of arrangements from around the country by my colleagues and me at The Century Foundation.

The AAUP toolkit advises faculty on how to evaluate proposed or existing agreements and advocate for better ones. The toolkit addresses issues central to AAUP members and their students, including intellectual property, consumer protection, contract payment and termination, and program governance. Although each is described below, the AAUP’s guidance is best taken as a package deal.

Intellectual Property

College and university arrangements with OPMs can include fine print that erodes or negates faculty control over the instructional materials they have created. The AAUP recommends that faculty groups scrutinize their institution’s intellectual property (IP) policy and advocate for stronger policies. To keep pace with the move to online education, it’s critical to retain faculty, college, or university ownership over IP if courses are offered online. Faculty should ensure that IP rights clarify ownership of course materials that are produced for online course use.

The 2012 contract between Rutgers University and Pearson’s OPM provides a positive example of IP rights being clearly spelled out.35 It not only defines IP but also gives examples of each of three types of IP that could result from the arrangement: Pearson IP, Rutgers IP, and jointly owned “Combined Work.” Importantly, the Rutgers IP example clearly states that Rutgers retains its IP even when Pearson has edited the work:

Rutgers IP example – Rutgers’ written material and media assets, including but not limited to images, graphs, interactive tutorials, podcasts, video lectures, simulations and animations. For purposes of clarity, content that is originated by a Rutgers professor which Pearson then edits, adapts, and/or formats such as Pearson recording a video lecture of a Rutgers professor or creating new iterations of a problem set or exam will be considered Rutgers IP.36

Consumer Protection

When evaluating agreements between their institutions and potential contractors, faculty should inquire what the marketing, recruiting, and enrollment processes will entail. Faculty should also be aware of whether or not their institution is paying an OPM on a tuition-sharing basis. Tuition sharing introduces an incentive for the OPM to engage in high-pressure recruiting and to emphasize marketing and outreach over other services promised in the contract. If such payment terms cannot or will not be avoided, faculty should advocate for close and constant control over marketing and recruiting activities. Contracts that delegate marketing to the contractor, but that do not include details on how, when, and who from the college or university will review marketing plans, advertising content, or recruitment scripts, are dangerous for students and for an institution’s reputation.

Once primarily the domain of for-profit colleges, restrictive enrollment contracts are now used by some public and nonprofit programs that are managed by OPMs.37 The worst enrollment contracts contain disturbing fine print that prevents students from exercising their rights if things go wrong. This is accomplished through so-called mandatory arbitration, go-it-alone, and gag clauses that bar students from pursuing damages in court, from joining class-action lawsuits, or from speaking about the complaint-resolution process. These restrictions are now appearing in the terms and conditions that apply to public and nonprofit college and university programs, especially in cases where institutions are paying an OPM to manage noncredit programs like coding bootcamps.38 Some such details are often found in the OPM contract, but usually there are separate terms and conditions the admitted students submit to, and it is equally important for faculty to be aware of these, since they are almost always developed by the third party.

Contract Payment and Termination

The most important elements of an outsourcing agreement are the payment terms and the conditions on which the contract can or will end. The payment terms establish the incentives of each party in the arrangement, and the most important element to look out for is tuition sharing. Institutions that pay contractors a percentage of revenue generated from the managed program(s) while also relying on those contractors to recruit students for admission create a scenario where the contractors will be incentivized to maximize enrollment and inclined to cut corners on other services. Likewise, the amount of revenue that is shared is important to consider. Faculty should compare the cost of contracting for discrete services with the eventual cost of a comprehensive OPM contract and ask themselves whether the percentage of tuition shared makes sense. Will the amount the college or university pays to the contractor prevent it from fully supporting faculty or otherwise ensuring online programs are on par with on-campus programs?

It is equally important that fair contract termination rights are included. The public institution must be able to get out of the contract with a reasonable amount of notice given and liability expected. Under no circumstances should a contract include automatic renewal clauses or restrictions on actions the institution can take upon termination.

Program Governance

An alarming finding of The Century Foundation’s analysis of contracts has been the prevalence of new program governance bodies formed via OPM agreements. These are sometimes referred to as steering committees, and they almost always provide equal parts and voting rights to the college or university and the OPM. Contracts reveal that some committees take up issues such as course offerings, class start dates, budgeting, tuition pricing, and enrollment targets. Allowing the OPM into discussions and decision making on any of these elements crosses a clear line into illegal territory. According to federal guidance, it is acceptable for a college or university to pay a contractor on a tuition-sharing basis only if the two parties are independent of each other—but steering committees eliminate that independence. While both parties stand to gain or lose revenue based on how the programs are managed, only one party—the OPM—has a primary interest in maximizing profits while taking part in steering committee discussions.39

For example, a four-member steering committee was formed as part of an agreement between Eastern Kentucky University (EKU) and Pearson, with the two parties being equally represented.40 However, meeting business could be conducted and votes could be made with just three members present. In theory, depending on meeting attendance, Pearson could steer the decisions being made for EKU’s managed programs. If the steering committee cannot resolve a dispute, the matter is turned over to Pearson’s chief executive officer and EKU’s president. These two individuals answer to vastly different governing boards with vastly different purposes, and their actions can have enormous consequences on students’ experiences and eventual livelihoods. Legality aside, there is no sound reason for an outsourcing agreement to create a steering committee that includes the paid contractor.

While there is no such thing as an ideal outsourcing agreement, the better among them respect the rights of faculty and students, maintain faculty control over academic governance, protect students from predatory recruiting, and keep the public institution intact by maintaining a safe distance between the college or university and the contractor.

The Century Foundation has continued to acquire and analyze agreements between public colleges and universities and their OPMs. This became all the more important when the COVID-19 pandemic sent entire campuses into virtual classrooms. Additional analysis has made it clear that there are even more questions faculty should consider as they advocate for better arrangements when outsourcing cannot be avoided.

- What are the short- and medium-term plans for using the services of the OPM? Faculty, through their governance structures, should reject arrangements with contract terms that go beyond the timeframe that represents one cohort of students.

- What are the enrollment goals behind the arrangement and whose goals are they? How many colleges, departments, and programs will be implicated in the arrangement? What is the justification for hiring an OPM for the program(s) of interest? Faculty should require a holistic analysis of the local and beyond-local demand for the programs from sources other than enrollment data. Likewise, faculty should require a full-scale analysis of the institution’s existing internal capabilities and a plan for building internal capacity if needed.

- What are the payment terms? Faculty should require evidence of revenue and expenditure modeling. If tuition sharing has been deemed necessary, it should be for a very limited time, the amount shared with the contractor should taper over time, and the contract should shift to fee-for-service terms within as short a timeframe as possible.

- How quickly and with what resources will the new programs launch? Do the plan and timeline match the process that would be used for creating and offering new on-campus programs?

- How many student start dates will be offered per year and why? Outsourced online programs have taken lessons from the for-profit college playbook, and some OPMs require their partners to offer multiple start dates per semester. To the prospective student, this is billed as a convenient feature that lessens the wait time between enrollment and the first day of class. However, there can be downsides to students, faculty, and the learning process when it comes to compressed semesters and quickly succeeding start dates. For the OPM, on the other hand, compressed schedules represent the ability to take in more cohorts (and revenue) per year and to move students through tuition cycles faster. Faculty groups should determine if they have a position on the number of start dates offered by their institution.

- What is the source of instructional labor for the new programs? Specifically, is the college or university remaining in control of instructor recruitment, onboarding, and training? Will the programs be staffed in a way that matches on-campus program staffing? At what benefit or expense? One strategy to erode faculty control over these matters is for online divisions to use completely different sources of labor, including by recruiting instructors who live in states other than that of the main campus. Faculty groups should require full transparency of the staffing plan for proposed programs.

- Are the outsourced programs replicas of programs that exist on campus already? Will the outsourced programs have parity with programs already offered on campus? Will instructors and students taking part in the online programs have access to the same resources as on-campus students? What is the plan for ensuring the new programs are as worthwhile to students as on-campus programs? These questions are important for faculty groups trying to determine whether the administration is creating access to an existing and worthwhile product or simply creating a potentially predatory, second-tier online campus with no meaningful connection to the institution.

- Will the college or university remain in control over marketing strategy and content? The most egregious outsourcing agreements assume the OPM has control over which materials and messages are used in advertisements. For example, a contract between Southeastern Oklahoma State University and Academic Partnerships assumes the university has approved marketing materials so long as the OPM attempts to share them.41 Instead, the agreement should have been written to give clear control to the university, especially since the university suffers the consequences for advertising taken out in its name. In general, if the contractor is responsible for creating and placing ad content, a defined process for the college’s or university’s active review and approval should be included.

- Student recruitment should be scrutinized. When services are paid on a tuition-sharing or commission basis, the inclusion of student recruiting is especially dangerous. Regardless of the payment terms, faculty should critically analyze the purpose of recruiting to fill virtual classrooms. If the documented demand for degrees, certificates, and other programs is real, could it be that online students would be just as likely to find their way to a physical campus as an online campus? Organic demand does not need to be drummed up. The reasons an online program might advertise go beyond organic demand. It could be that a college or university is specifically looking for students who do not live near the campus. This could be a losing game, since recent data indicate that 82 percent of online-only students who are enrolled in public colleges and universities live in the same state as their institution.42 Alternatively, if colleges and universities hope to pull students who might attend a for-profit college, faculty should ask the decision makers how their institution’s online degree offers something different to students who would otherwise enroll in a national for-profit. If the answer is that students get degrees bearing the public institution’s name, then the institution is complicit in renting out its own brand. Faculty groups from public and nonprofit colleges and universities should work to address this problem at its root by curbing spending on advertising and recruiting by the for-profit sector.

Unfortunately, faculty and students can exist on a campus without knowing they have tens of thousands of peers in the virtual space. Online students—and especially prospective online students—are invisible and easy to overlook, making them a prime target for profiteers who operate under the guise of providing a public service. This invisibility increases the sense that the public is truly on the losing end of so-called public-private partnerships in online higher education.

Until the public is reaffirmed as part of public-private partnerships, prospective students should assume there are private actors with incentives that run counter to the purpose of public higher education. Reclaiming the public aspect, even in contexts where outsourcing has been normalized, is essential to meeting public institutions’ democratic mission of education for the common good.

Stephanie Hall is a senior fellow at The Century Foundation. Previously, she worked at the University System of Maryland Office of Academic and Student Affairs, where she focused on teacher education, workforce development, civic education, and undergraduate student equity in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics. Early in her career, she was a middle and high school teacher in the Atlanta area and in Brazil.

*Traditional undergraduate college students are often thought of as those under the age of 25 who enter college immediately following high school and attend full time, while nontraditional students are those whose prior experiences, opportunities, and choices may diverge from that.2 (return to article)

†To understand why wages have been stagnant and what we can do about it, see “Moral Policy = Good Economics: Lifting Up Poor and Working-Class People—and Our Whole Economy” in the Fall 2021 issue of American Educator. (return to article)

Endnotes

1. National Center for Education Statistics, “Table 311.22. Number and Percentage of Undergraduate Students Enrolled in Distance Education or Online Classes and Degree Programs, by Selected Characteristics: Selected Years, 2003–04 Through 2015–16,” Digest of Education Statistics, US Department of Education, 2018, nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d18/tables/dt18_311.22.asp.

2. See National Center for Education Statistics, “Nontraditional Undergraduates: Definitions and Data,” US Department of Education, nces.ed.gov/pubs/web/97578e.asp.

3. R. Seltzer, “Purdue Faculty Questions Kaplan Deal,” Inside Higher Ed, May 5, 2017.

4. R. Shireman and Y. Cao, “Purdue University Global Is a For-Profit College Masquerading as a Public University,” The Century Foundation, August, 28, 2018.

5. J. Steinberg, “UA Acquires For-Profit Ashford University, Launches New Online ‘Campus,’ ” Arizona Public Media, December 1, 2020; L. McKenzie, “University of Arizona’s Big Online Push,” Inside Higher Ed, August 4, 2020; and J. Young, “U. of Arizona Bought a For-Profit U. for $1? Actually, the For-Profit Paid Millions to Be Acquired,” EdSurge, August 6, 2020.

6. Data as of December 21, 2021: S. Hall, “How Far Does Your Tuition Dollar Go?,” The Century Foundation, April 18, 2019, updated January 14, 2022.

7. Data as of December 21, 2021: Hall, “How Far?” For medians, search an institution and then data for comparisons will be provided along with the institution’s data.

8. College Scorecard, “Ashford University,” US Department of Education, collegescorecard.ed.gov/school/?154022-Ashford-University.

9. Jamienne Studley to Paul Pastorek, July 30, 2021, wascsenior.app.box.com/s/b8stysp3pfmopfy6b93gfsbo4dl5y9bt.

10. Veterans Education Success, “Law Enforcement Actions Against Predatory Colleges,” January 2021; and Office of the Attorney General, “Attorney General Bonta Continues Fight to Hold Ashford University Accountable for Defrauding and Deceiving California Students,” State of California Department of Justice, press release, November 8, 2021.

11. For a comprehensive collection of public institution-OPM contracts as of August 2021, see this report and appendix: S. Hall and T. Dudley, Dear Colleges: Take Control of Your Online Courses (New York and Washington, DC: The Century Foundation, September 12, 2019).

12. R. Rich, “The Great Recession: December 2007–June 2009,” Federal Reserve History, November 22, 2013, federalreservehistory.org/essays/great-recession-of-200709.

13. S. Laderman and K. Heckert, SHEF: State Higher Education Finance, FY 2020 (Boulder, CO, and Washington, DC: State Higher Education Executive Officers Association, 2021).

14. V. Yuen, The $78 Billion Community College Funding Shortfall (Washington, DC: Center for American Progress, October 7, 2020); and D. Smith, Achieving Financial Equity and Justice for HBCUs (New York and Washington, DC: The Century Foundation, September 14, 2021).

15. S. Hall, The Students Funneled Into For-Profit Colleges (New York and Washington, DC: The Century Foundation, May 11, 2021).

16. D. DeSilver, “For Most U.S. Workers, Real Wages Have Barely Budged in Decades,” Pew Research Center, August 7, 2018.

17. J. Mishory, M. Huelsman, and S. Kahn, How Student Debt and the Racial Wealth Gap Reinforce Each Other (New York and Washington, DC: The Century Foundation, September 9, 2019).

18. R. Daniels, “Universities Are Shunning Their Responsibility to Democracy,” The Atlantic, October 3, 2021.

19. National Center for Education Statistics, “Graduate Degree Fields,” US Department of Education, May 2021, nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator/ctb.

20. 2003–16 stats are from National Center for Education Statistics, “Table 311.32. Number and Percentage of Graduate Students Enrolled in Distance Education or Online Classes and Degree Programs, by Selected Characteristics: Selected Years, 2003–04 Through 2015–16,” nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d17/tables/dt17_311.32.asp. 2019 stats are from National Center for Education Statistics, “Postbacclaureate Enrollment,” US Department of Education, May 2021, nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator/chb?tid=74.

21. US Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions, “Apollo Group, Inc.,” in For Profit Higher Education: The Failure to Safeguard the Federal Investment and Ensure Student Success (Washington, DC: US Senate, July 30, 2012), help.senate.gov/imo/media/for_profit_report/PartII/Apollo.pdf.

22. E. Hanford, “The Case Against For-Profit Colleges and Universities,” American Public Media, 2012.

23. Hall and Dudley, Dear Colleges.

24. Hall and Dudley, Dear Colleges.

25. See Eastern Michigan University’s contract with Academic Partnerships: Academic Partnerships and Eastern Michigan University, “Service Agreement,” September 1, 2016, drive.google.com/file/d/1D7ChmFr2Lj9wDSukkM60HXcb9r0KE7Sa/view; Louisiana State University Shreveport’s contract with Academic Partnerships: Academic Partnerships and Board of Supervisors of Louisiana State and Agricultural and Mechanical College, “Consulting Contract: LSUS Contract No. 1565,” January 7, 2013, with addendums no. 1–8, s3-us-west-2.amazonaws.com/production.tcf.org/assets/OPM_contracts2/Louisiana+State+University+Shreveport+%26+Academic+Partnerships.pdf; and the University of West Florida’s contract with Academic Partnerships: Academic Partnerships and University of West Florida, “License and Distribution Agreement,” May 27, 2011, s3-us-west-2.amazonaws.com/production.tcf.org/assets/OPM_contracts2/University+of+West+Florida+%26+Academic+Partnerships.pdf.

26. E. Ochoa, “Implementation of Program Integrity Regulations,” DCL GEN-11-05, US Department of Education, Federal Student Aid, March 17, 2011, fsapartners.ed.gov/knowledge-center/library/dear-colleague-letters/2011-03-17/gen-11-05-subject-implementation-program-integrity-regulations.

27. R. Shireman, “The Sketchy Legal Ground for Online Revenue Sharing,” Inside Higher Ed, October 30, 2019.

28. Holon IQ, “Global OPM and OPX Market to Reach $13.3B by 2025,” March 3, 2021.

29. Hall and Dudley, Dear Colleges.

30. S. Hall, Invasion of the College Snatchers (New York and Washington, DC: The Century Foundation, September 30, 2021).

31. T. Dudley et al., Outsourcing Online Higher Ed: A Guide for Accreditors (New York and Washington, DC: The Century Foundation, June 28, 2021).

32. R. Shireman, How For-Profits Masquerade as Nonprofit Colleges (New York and Washington, DC: The Century Foundation, October 7, 2020).

33. Hall, Invasion.

34. American Association of University Professors, “Anti-Privatization Work,” aaup.org/issues/anti-privatization-work.

35. Rutgers University and eCollege.com, “Managed Online Programs Agreement Between Rutgers University and eCollege.com,” September 17, 2012, drive.google.com/file/d/1CBVlSSGvfHRd9_KtiJXkK1GQvLGsApra/view?usp=sharing.

36. Rutgers and eCollege.com, “Managed Online Programs Agreement.”

37. T. Habash and R. Shireman, How College Enrollment Contracts Limit Students’ Rights (New York and Washington, DC: The Century Foundation, April 28, 2016).

38. T. Dudley and E. Rindlisbacher, Flying Under the Regulation Radar: University Partnerships with Coding Bootcamps (New York and Washington, DC: The Century Foundation, August 4, 2021).

39. Hall and Dudley, Dear Colleges.

40. See contracts between Eastern Kentucky University and Pearson: Eastern Kentucky University and Compass Knowledge Group, “Online Education System Master Agreement: For Eastern Kentucky University RFP 23-10,” December 21, 2005, production.tcf.org.s3.amazonaws.com/assets/OPM_contracts/EasternKentuckyUniversity_Pearson.pdf; and Eastern Kentucky University and Embanet-Compass Knowledge Group, “Standard Contract for Personal Services,” April 28, 2020, drive.google.com/file/d/1EIcko5qrKn7ippGxSGPhrS1fdibGXt8M/view.

41. Academic Partnerships and Southeastern Oklahoma State University, “Service Agreement,” December 15, 2015, s3-us-west-2.amazonaws.com/production.tcf.org/assets/OPM_contracts2/Southeastern+Oklahoma+State+University+%26+Academic+Partnerships.pdf.

42. National Center for Education Statistics, “Distance Education in College: What Do We Know from IPEDS?,” NCES Blog, February 17, 2021.

Illustrations by Pep Montserrat