High school students with reading difficulties face incredible challenges navigating content learning. Content-area teachers in disciplines such as social studies seek to cultivate students who can identify and communicate key ideas, provide explanations of and evidence for these ideas, and evaluate differing perspectives on a topic by assessing evidence and claims. These crucial goals require active engagement of students to obtain a great deal of new content knowledge and to assimilate it with their existing background knowledge. In addition, students need to learn and use the language of the discipline, read and understand text within the discipline, and actively apply their newly obtained knowledge to reasoning and decision-making tasks.

However, across the United States there are students in nearly every class who have not achieaved proficiency in reading by the time they enter high school.1 These students face significant barriers in preparing for college, for careers with livable wages, and for civic engagement.

Social studies teachers also face significant challenges; it is very difficult to meet all students’ needs when some can easily learn independently from text and others require extensive supports to understand text adequately. The data from a recent study with 11th-grade social studies classes revealed that disparities between students are often quite stark: fall reading achievement scores in a typical class spanned more than 2.5 standard deviations of reading achievement,2 which means reading achievement in many classes can span more than 70 percentile points (e.g., 9th percentile to 82nd percentile). With such a wide range of reading abilities in their classes, it was impossible for those social studies teachers to focus solely on the content and discourse of the primary and secondary text sources in their curricula. Although there is enormous variety among high school students with limited literacy, many have some foundational word-reading skills* but may struggle with text because of its vocabulary, structure, or length; they may also have difficulty making connections and inferences in the text, in part because they lack assumed background knowledge or effective strategies for monitoring their comprehension of the text while reading.

How can a teacher address the needs of students who are not proficient readers at the same time they are trying to teach a mountain of content? Although it is critical that students with reading difficulties receive appropriate interventions outside of the social studies classroom to improve their reading achievement, embedding disciplinary literacy within the content may help teachers address the diverse needs of students and stay focused on the important content they are teaching. In truth, most students (even many who are strong readers) need instruction in successfully reading and understanding text in specific disciplines.3 For example, a historian may read a diary entry by a famous politician skeptically (i.e., is she intentionally writing for posterity?), but take a diary entry by a not-famous waitress in a small town at face value. Likewise, a historian would consider related factors, such as when and where each diary entry was written, what ideas and events were prominent locally and globally, and other issues that may have affected the writers. Then, there are the vocabulary, structure, and other text-specific aspects of historical reading.

Embedding discipline-specific literacy instruction within social studies content can assist a variety of students, including those with reading difficulties, to build higher-level reading abilities, increase knowledge acquisition, and improve their overall content learning. Moreover, many state learning standards already address the need for discipline-specific literacy instruction in content areas such as social studies.4

Enhancing Students’ Comprehension in Social Studies

So, what are some instructional practices that can feasibly be embedded in the content, that enhance (and do not detract from) the content, and that have demonstrated the ability to improve students’ content understanding? The research on adolescent academic literacy suggests several recommendations, such as providing support for students to read and comprehend increasingly complex text, offering explicit instruction in vocabulary and concepts that are a part of the discipline and text reading, and engaging students in content and text discussions to promote higher-level reasoning and critical thinking.5

Based on this body of research, five instructional practices are outlined below. Social studies teachers can embed these practices into their existing instruction to further engage students in the subject matter and provide support for discipline-specific reading. Middle and high school social studies teachers who have embedded these instructional practices in their units consistently see increased student content knowledge as compared with typical instructional practices,6 including for students with disabilities.7

Start with a Comprehension Canopy

The comprehension canopy serves as a unit starter and consists of three very brief components: establishing a purpose, asking an overarching question, and priming initial background knowledge. At the beginning of each instructional unit, teachers provide a purpose for the upcoming unit and readings, along with an overarching question to guide comprehension during the unit. This question is revisited throughout the unit as students learn new content that addresses the question. Therefore, the question gives students an explicit organizer for the content they are learning. The question should be broad and cover the key ideas from the unit so that students can organize the critical information they learn to fully address the question by the end of the unit. For example, in a unit on the Gilded Age, the unit question may be “During the Gilded Age, how did the economic, political, and social landscape of America change?”

Teachers also provide a brief introduction to the unit, to build some background knowledge about the upcoming content. When possible, it is helpful for this introduction, or part of it, to be provided in a short video (of three to five minutes). Videos should provide information about at least one key concept that will be covered in the unit and be chosen to pique student interest in learning the content of the unit. Students briefly discuss a prompted question or two about the video with a partner to process the video. Questions can help students make connections between their knowledge and the content of the video and the upcoming unit. For example, to introduce a unit on the Gilded Age, a teacher may start with a video about Ellis Island and provide questions such as “Who in your family was the first to come to America?” and “Why did they leave their native land to come here?” Or a teacher may decide to connect to the perspective of the people in the video, asking “Imagine you were the first in your family to come to America. Why might you choose to leave your native land to come here?” To prepare for their discussion, students could write at least two reasons a person might have immigrated to America. That discussion concludes the comprehension canopy, which is intended to be simple and brief (taking only 7 to 10 minutes) to provide a framework to engage students in the upcoming content.

Teach Essential Content-Specific Words and Concepts

Another beginning-of-the-unit instructional practice is to explicitly introduce four or five essential words or concepts necessary for understanding the content of the unit. Explicit vocabulary instruction benefits students’ comprehension of material, particularly for students with reading difficulties.8 Selection of these words should consider usefulness and importance in the discipline. For example, the word revenue is an important and useful word in many social studies units. It may be essential for a student to fully understand this word if they are to engage in discourse and analysis of the social studies discipline. As a result, revenue may be selected as an essential word to explicitly teach students. Often, teachers provide the essential word instruction right after completing the comprehension canopy to help increase equity in terms of vocabulary and background knowledge before any other unit content is taught.

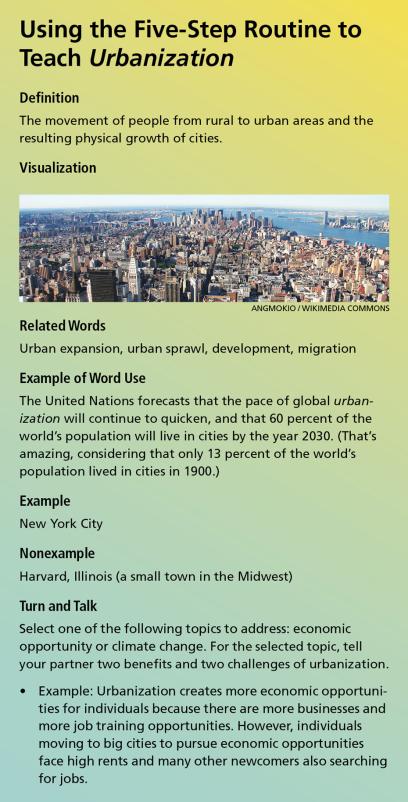

After selecting the essential words for the unit, explicit instruction is provided in the meaning and the use of the words. Research on learning new words and concepts points to the importance of providing instruction beyond just definitions of the words.9 The following five-step routine is an effective way to introduce and discuss each word. It usually takes a total of 15 to 20 minutes.

- Provide a student-friendly definition.

- Show a visual representation of the word to help students remember its meaning.

- Present related words to help students make connections between the new word and other known words.

- Discuss examples and nonexamples of the word or word use.

- Prompt pairs of students to discuss and apply the meaning of the word.

The box on the right provides an example of this routine for the word urbanization.

Research on vocabulary learning suggests students need repeated exposure to new words and opportunities to apply their word knowledge in order to retain the word or concept in their vocabulary.10 Accordingly, essential words should be used throughout the unit, including in the texts students will be reading. Essential words can also be reviewed through short warm-up activities at the beginning of several class periods throughout the unit. These warm-up activities are developed to allow the students to work independently for two to three minutes to apply word knowledge within the content. For example, after students have been learning and reading about the pros and cons of urbanization, a warm-up activity to review and apply the word might include students examining a photograph of a large urban area that they have been studying and then writing one challenge of urbanization and a potential solution in each of several areas (e.g., environment, public health, housing, transportation, employment). Warm-up activities can be spread out over the course of the unit, with each of the essential words and concepts reviewed in this mode at least once during the unit.

Provide Support for Critical Content Readings

The critical readings instructional practice helps ensure that all students, even those who are still developing as readers, work through and comprehend content within primary and secondary text sources. In order to provide sufficient support for the varying levels of readers in the class, critical readings happen during class time and typically require approximately 20 minutes.

To begin a reading, teachers provide a brief introduction that sets the context. This introduction can include emphasizing essential words students will encounter and connecting the information they will read to the overarching question for the unit. For example, building on the question “During the Gilded Age, how did the economic, political, and social landscape of America change?,” a teacher may say, “In this reading, we will learn about some of the economic issues facing workers during the Gilded Age.” Students can read the text as a whole class with the teacher, in small groups, in pairs, or independently. Depending on students’ needs, teachers may also divide the class, with some reading independently and others reading as a group with teacher support. Even when teachers are assisting, it is important that students do the majority of the reading (rather than the teacher or another student reading it to them). Students can only gain practice in reading and understanding content-area text independently if they are actually reading.

Teachers guide the students to stop in two to three predetermined places in the text (e.g., after one to two paragraphs or one section) to monitor comprehension of the text. At these stopping points, students answer key text questions about the text read thus far, verbally or in writing (e.g., In what ways does the author seem to feel that immigrants were once important to the American economy? How does the author feel labor conditions have now changed?), and briefly discuss responses before continuing the reading. Discussions should be brief and focused on the reading and the text question, rather than a time to provide an extended lecture on the content. The teacher also leads a debriefing of the whole text after the reading is completed. The critical readings routine is typically used two to three times during a two-week unit.

Use Teams to Monitor Content Understanding

Team-based learning, a practice first used in higher education and adapted for middle and high school,11 involves the use of heterogeneous, permanent teams of students (three to five students at the high school level) to discuss and apply content throughout the unit. One use of these teams is to monitor student understanding and learning of the content using comprehension checks. These occur a couple of times during each unit and are designed to take about 15 minutes, with an additional 5 minutes for targeted instruction.

How are comprehension checks implemented? A short quiz (about five multiple-choice questions) of the content and vocabulary learned in the unit thus far is given to all students. Teachers intentionally develop questions that do have a correct answer, but require students to integrate and evaluate key aspects of the curriculum. For example, rather than asking “What is urbanization?,” a teacher may ask “Which of the following is not a cause of rapid urbanization during the Gilded Age?,” requiring students to integrate their knowledge of urbanization with the causes during the Gilded Age.

Students first complete the quiz individually and turn it in to the teacher. This provides the teacher with information on individual student understanding and retention of the unit content covered. Next, students get into their teams and answer the same questions again. Because the questions have been carefully crafted to draw on multiple aspects of the content, they are likely to elicit discussion of the content during the team work. In addition, because each student has already taken the quiz, each is prepared to contribute to the discussion.

During the teams’ work on the quiz questions, they are allowed to use their texts and notes from class to find evidence supporting their answers. The teams discuss each question and come to consensus on an answer with their evidence. As teams mark their answers, they receive immediate feedback from a scratch-off card or a digital version of the quiz (that, like a scratch-off, only indicates whether an answer is right or wrong). If a team does not get the correct answer, they go back to discussing the question with their text and notes until they come to consensus on another answer. The teacher moves between teams as they discuss, facilitating their use of evidence and reasoning. The teacher can also identify any misunderstandings or content gaps in the students’ discussions. The teacher collects the scratch-off cards or digital results when the teams are finished, particularly to examine questions that took teams multiple attempts before obtaining the correct answer.

Together, these individual and team comprehension checks provide information on students’ understanding of the content thus far and their readiness for content application activities. The teacher uses the information from the individual answers, discussions, and team answers to plan individual, small-group, or whole-class instruction that is targeted to address knowledge gaps.

Use Teams to Apply Content Knowledge

At the end of the unit, students apply the knowledge they have acquired. Students once again work in their teams to integrate the unit content in a problem-solving or perspective-taking activity. Because the activity is designed to elicit discussion and decision making using the content from the unit, prompts are complex. For example, teams may be asked to “Imagine you serve on an advisory committee to a Gilded Age president. As a team, make a recommendation regarding whether the United States should limit immigration. Provide at least two economic, two political, and two social reasons in support of your recommendation.” Each team discusses each aspect of the task; identifies evidence or support for their reasoning from their notes, readings, and other class resources from the unit; and records key information.

Providing graphic organizers—such as a table for each of the unit readings on immigration where students can identify the author’s perspective, audience, general argument, and supporting evidence—and breaking the task into clear steps can help high school students work through the activity effectively. By the end of the activity, each team prepares a written response stating their decision and rationale (e.g., the team’s recommendation and their economic, political, and social support points). Coming back together as a whole class, the teams report on their conclusions and rationales. The teacher highlights high-quality use of text to support ideas, requires teams to report on their text evidence when it is lacking, and facilitates student questions about a team’s conclusions. Key connections between the activity, the student conclusions, and the overarching question are then discussed to bring closure to the unit. Finally, the teacher facilitates an evaluation of the team process and success working together. For example, each team member might rate their team or their peers on items such as use of text-based evidence, active contributing, active listening, critical thinking, or teamwork.

Together, consistently using this set of practices to provide instruction for each content unit can help all students, including students with reading difficulties, read and understand the content as well as fully engage in the content. These practices ensure students engage in not only knowledge acquisition but also the application of that knowledge. The table below provides a summary of the activities within each instructional practice.

Students with reading difficulties need continuity in the supports they are provided across their academics in order to succeed in high school. A reading difficulty should not mean that students have to fall behind in their other academic areas. Social studies teachers can substantially raise achievement when they have the tools to engage and support a variety of students in learning their discipline.

Jeanne Wanzek is the Currey-Ingram Endowed Chair and a professor in the Department of Special Education at Peabody College of Vanderbilt University. A former special education and elementary school teacher, she researches effective reading instruction, intervention, prevention, and remediation for students with reading difficulties and disabilities.

*For more on foundational literacy skills, see “Teaching Reading Is Rocket Science” in the Summer 2020 issue of American Educator. (return to article)

Endnotes

1. Carnegie Council on Advancing Adolescent Literacy, Time to Act: An Agenda for Advancing Adolescent Literacy for College and Career Success (New York: Carnegie Corporation of New York, 2010); and National Center for Education Statistics, US Department of Education, National Assessment of Educational Progress Report Card, 2019, nces.ed.gov/nationsreportcard.

2. J. Wanzek et al., “Promoting Acceleration of Comprehension and Content Through Text in High School Social Studies Classes,” Journal of Research on Educational Effectiveness 8 (2015): 169–188.

3. C. Lee and A. Spratley, Reading in the Disciplines: The Challenges of Adolescent Literacy (New York: Carnegie Corporation of New York, 2010).

4. Common Core State Standards Initiative, Common Core State Standards for English Language Arts & Literacy in History/Social Studies, Science, and Technical Subjects (Washington, DC: 2010), corestandards.org/wp-content/uploads/ELA_Standards1.pdf.

5. See, for example, Carnegie Council on Advancing Adolescent Literacy, Time to Act; R. Heller and C. Greenleaf, Literacy Instruction in the Content Areas: Getting to the Core of Middle and High School Improvement (Washington, DC: Alliance for Excellent Education, 2007); Lee and Spratley, Reading in the Disciplines; National Association of Secondary School Principals, Creating a Culture of Literacy: A Guide for Middle and High School Principals (Reston, VA: 2005); and J. K. Torgesen et al., Academic Literacy Instruction for Adolescents: A Guidance Document from the Center on Instruction (Portsmouth, NH: RMC Research Corporation, Center on Instruction, 2007).

6. S. Vaughn et al., “Improving Reading Comprehension and Social Studies Knowledge in Middle School,” Reading Research Quarterly 48 (2013): 77–93; S. Vaughn et al., “Improving Middle-School Students’ Knowledge and Comprehension in Social Studies: A Replication,” Educational Psychology Review 27, no. 1 (2015): 31–50; S. Vaughn et al., “Improving Content Knowledge and Comprehension for English Language Learners: Findings from a Randomized Control Trial,” Journal of Educational Psychology 109, no. 1 (2017): 22–34; J. Wanzek et al., “The Effects of Team-Based Learning on Social Studies Knowledge Acquisition in High School,” Journal of Research on Educational Effectiveness 7 (2014): 183–204; and Wanzek et al., “Promoting Acceleration of Comprehension.”

7. S. C. Kent et al., “Team-Based Learning for Students with High-Incidence Disabilities in High School Social Studies Classrooms,” Learning Disabilities Research and Practice 30 (2015): 3–14; E. Swanson et al., “Improving Reading Comprehension and Social Studies Knowledge Among Middle School Students with Disabilities,” Exceptional Children 81, no. 4 (2015): 426–442; and J. Wanzek et al., “English Learner and Non-English Learner Students with Disabilities: Content Acquisition and Comprehension,” Exceptional Children 82, no. 4 (2016): 428–442.

8. A. M. Elleman et al., “The Impact of Vocabulary Instruction on Passage-Level Comprehension of School-Age Children: A Meta-Analysis,” Journal of Research on Educational Effectiveness 2, no. 1 (2009): 1–44.

9. I. L. Beck and M. G. McKeown, “Increasing Young Low-Income Children’s Oral Vocabulary Repertoires Through Rich and Focused Instruction,” Elementary School Journal 107, no. 3 (2007): 251–271; M. D. Coyne, D. B. McCoach, and S. Kapp, “Vocabulary Intervention for Kindergarten Students: Comparing Extended Instruction to Embedded Instruction and Incidental Exposure,” Learning Disability Quarterly 30, no. 2 (2007): 74–88; and T. S. Wright and G. N. Cervetti, “A Systematic Review of the Research on Vocabulary Instruction That Impacts Text Comprehension,” Reading Research Quarterly 52 (2017): 203–226.

10. J. F. Baumann, “Vocabulary and Reading Comprehension: The Nexus of Meaning,” in Handbook of Research on Reading Comprehension, ed. S. E. Israel and G. G. Duffy (New York: Routledge, 2009), 323–346.

11. L. K. Michaelsen and M. Sweet, “Team-Based Learning,” New Directions for Teaching and Learning 128 (2011): 41–51; Vaughn et al., “Improving Reading Comprehension”; and Wanzek et al., “The Effects of Team-Based Learning.”

[illustrated by David Vogin]