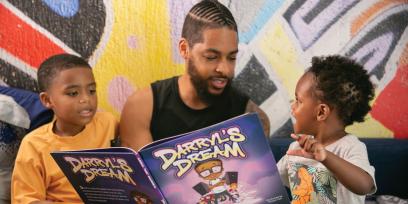

Helping your child learn to read is important—and can feel overwhelming. Even if you are able to talk to your child’s teacher often, you probably still have questions about literacy. Wanting to help answer those questions, we partnered with the National Parent Teacher Association to get a list of questions from parents for reading teachers. Then, we brought together a group of current teachers and teachers-turned-researchers to answer them. You are your child’s first and most important teacher; we hope this guide helps you feel confident as you help your child develop a love of reading.

–EDITORS

1. What are the building blocks of literacy?

The original building block of literacy is early oral language, representing children’s developing capacity to understand and produce the words and sentence structures of the language(s) they speak. Oral language skills, including an ever-expanding vocabulary, are critically important for literacy. They are one of the necessary foundations underneath successful reading comprehension. The stronger children’s oral language skills, the more readily they will be able to comprehend what they read.

Another necessary foundation for reading comprehension is skilled word reading, including automatic recognition of familiar words and the ability to “decode” or sound out unfamiliar words. How is skilled word reading developed? One building block that leads to skilled decoding is alphabet knowledge—matching the printed forms and sounds of each letter. Another building block that supports skilled decoding is the ability to identify and manipulate the sounds within words. Together, these two foundational skills allow children to “crack the code” and begin decoding: first simple one-syllable words, then more advanced words with multiple syllables and more complex spelling patterns. The more words children successfully decode, the more words they automatically recognize the next time they see them, and the more fluent their reading becomes.

All along the way, children are drawing upon their language skills to help them decode and comprehend what they are reading. As text becomes more complex, these oral language skills become increasingly relevant. This is why it is so important to support children’s language skills before, while, and after they learn to read.

2. When can you really tell that literacy is hard for your child?

Learning to read takes many years, so it can be hard to tell if your child is on track or needs extra support. Among young children, early signs that learning to read may be challenging for a child include difficulties with oral language, with manipulating sounds within words, and with learning the alphabet. These and other things to look for in three- to five-year-old children are described by Beth M. Phillips here.

For more details on the phases that children move through as they learn to read, see Linnea C. Ehri’s article here. If your child does not seem to be progressing steadily through these phases, see the article by Sharon Vaughn and Jack M. Fletcher on helping children who are struggling readers, here.

It is also important to recognize that some children who do not have trouble learning to decode may still face challenges with reading comprehension. See Sonia Q. Cabell’s article here, where she discusses what early instruction should look like to support comprehension. Also see Natalie Wexler’s article here about supporting comprehension and knowledge acquisition through conversations about what you are reading with your child.

3. How important is fluency? And when should children stop working on fluency?

Fluency becomes important as soon as children begin to read texts and stays important even for proficient readers. Fluency is the ability to read accurately, quickly, and with appropriate expression. Fluency supports comprehension. When children become fluent readers, they read with ease and their reading sounds a lot like their talking. Fluency frees the reader to think about the meaning of the text. If a child reads slowly and haltingly, having to focus on sounding out words, then it is very hard to understand the information and ideas shared in the sentences. Fluency also represents comprehension. When you read out loud, you vary your tone of voice and pause at the right times; this indicates that you are understanding the text, and it helps listeners understand too.

By the end of elementary school, children should be able to read relatively simple chapter books and informational texts fluently—but they may need to practice reading more complex texts easily and accurately. This remains true even for advanced readers. When advanced readers encounter new texts with many rare words, especially multisyllabic words, their typically fluent reading may slow down. Complex sentence structures can also be a challenge to fluent reading. Practicing a text several times can assist with presenting it fluently to others.

If your child can correctly sound out words but does so with difficulty, they need more practice reading. As Diane August recommends in Spanish here (and in English here), “ask your child’s teacher for texts that your child can practice reading aloud to you every night.”

4. How does technology help literacy skills?

Technology can support children who are learning to read in a variety of ways. Elementary school teachers often use programs that range from helping a child sound out a specific word to reading a whole book to a child. Programs like these offer practice and individualized help while the teacher is busy with other children. Many computer programs and apps are also available to support children with specific needs. They can include accessibility features that remove barriers that children may otherwise face in accessing print.

However, technology does not replace the need for children to be taught and encouraged by caring adults—you, other family members and caregivers, and teachers. Not all technology is created equally. For example, sometimes technology can have features that are distracting, such as buttons during a read-aloud that don’t support the meaning of the story. Also, when it comes to children’s learning, there is no substitute for warm and responsive back-and-forth conversations and interactions.

5. How is literacy connected to writing?

There is a reciprocal relationship between reading and writing. In fact, literacy researchers and teachers talk about decoding (sounding words out) and encoding (spelling words). Both rely on the same foundational knowledge: knowing the sounds that make up words and the letters that represent those sounds. At the same time, practice in writing helps children build their reading skills. This is especially true for younger children. As they are learning how letters represent sounds and how to sound words out, it’s helpful to also practice spelling words.

When children read extensively, they also become better writers. Reading a variety of genres (e.g., science fiction, memoirs, and poetry) helps children learn text structures and language that they can transfer to their own writing in other formats (e.g., a short story or a persuasive essay). In addition, reading provides young people with background knowledge that they can use when they write.

To help your three- to six-year-old start writing, check out the tips offered by Nell K. Duke here. And to help your elementary school child become a better writer, turn to the article by Judith C. Hochman, Toni-Ann Vroom, and Dina Zoleo here.

6. There is a saying that after third grade, children are no longer learning to read but are reading to learn. Why is that, and is it too late to develop reading skills?

A child doesn’t need to wait until third grade to read to learn about the world around them. In fact, it is never too early to start developing the skills that set the stage for reading to learn! It’s true that educators must focus on teaching children foundational reading skills in the beginning of elementary school so they become confident readers (and writers) during elementary school. Linnea C. Ehri explains the phases of foundational skill development here. But foundational skills alone won’t prepare your child to read to learn—that also requires oral language and knowledge development. Even before children can fluently decode words, they can learn through listening to books read aloud by teachers, parents, and other caregivers. The language of books is more formal than the language we use in daily conversations and often includes vocabulary we don’t usually use while speaking. Also, the conversations that take place before, during, and after reading aloud are important to children’s learning. Learn how to help your child understand texts in the articles by Sonia Q. Cabell here and Natalie Wexler here.

Thankfully, it is never too late to develop reading skills! Even with good early instruction, some children in later grades face significant difficulties learning to read. With explicit instruction, practice, and support, they can make great strides. If your child is struggling to read, stay determined and hopeful—and see the article by Sharon Vaughn and Jack M. Fletcher here.

7. Why does dyslexia seem to be diagnosed more than it used to be, and why doesn’t that immediately mean children need services?

There is increased awareness about dyslexia that may be leading to more children being diagnosed. Providing initial screenings of all children allows schools to identify those who may need additional evaluation to determine whether they should receive a dyslexia diagnosis. Early diagnosis is especially critical for helping children with reading challenges and disabilities, including dyslexia. Timely diagnosis enables children to receive focused, evidence-based instruction that meets their needs. Diagnosis also ensures that children receive appropriate accommodations within the school setting.

As Sharon Vaughn and Jack M. Fletcher discuss, there is a wide range of skills among children who have dyslexia. Therefore, not all will require the same level or type of supportive services. High-quality instruction and intervention for all children, including those with dyslexia, meet children where they currently are and help them to advance their reading skills. To learn how you can partner with your child’s teacher in this process, turn to the article by Vaughn and Fletcher here.

[photos: Suzannah Hoover and Bob Riha, Jr.]

Member Benefits

Member Benefits Find Your Local

Find Your Local How to Join

How to Join En Espanol

En Espanol